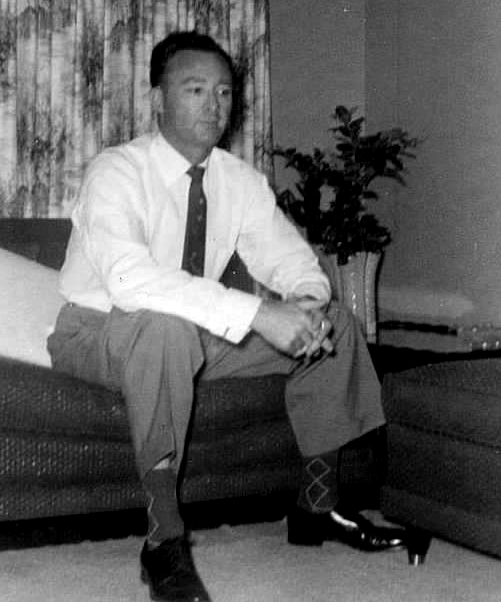

Carl Taylor

By Angelo Cohn Contributing Writer, Contributing Writer

CCIDI AMIN came to the airport on a bicycle I to meet us, and it was pretty

obvious he knew why we were there," Carl Taylor said in recounting the

flying job to bring the Uganda president’s Westwind jet back to its

Israeli builders.

The unusual flying assignment came just two months after the 4th of July Israeli

raid to free more than 100 hostages from an Air France jet that was hijacked

and ended up at Entebbe, Uganda’s airport. Taylor, a professional pilot

from MSP (Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota) was thoroughly familiar with the

Westwind, having flown the same type of aircraftwhen it was called the Jet

Commander before North American Rockwell licensed it to Israel Aircraft Industries.

“That Uganda thing wasn’t exactly your everyday corporate pilot

job,” Taylor admitted to Pro Pilot. But it did include numerous operational

details which reflect the “fly on demand” syndrome that makes

corporate aviation different from scheduled flying for the airlines. Taylor

preferred to confine his comments on the aviation elements of the Uganda mission

for the benefit of corporate pilot friends and let the general news media

speculate about the political implications. But he does have a briefcase full

of clippings from newspapers of several countries and as many languages probing

the political angles. Those accounts vary from paper to paper and country

to country, but the essential details are similar. They report that a West-

wind B-model jet was either given or sold on liberal credit by Israel Aircraft

to Idi Amin. At that time the Ugandan president was friendly to the Jewish

state, received paratrooper training there, and did business frequently with

Israel. There is general agreement, too, that Amin was so embarrassed by the

Air France hijack incident and the raid to release the hostages that he realized

he’d have to give the aircraft back to Israel to clear the books. But

he didn't know how to do it without further embarrassment.

That's a fair capsule of the media reports. Taylor’s part in the international

drama started like so many other corporate assignments—with a phone

call inquiring about his availability for a big rush flying job. The caller

was Peter Demos, another MSP pilot who has ferried more than 150 light planes

to Europe and knew of Taylor’s long experience as a Jet Commander corporate

pilot. He was calling from Switzerland, where he wanted Taylor to join him

“ immediately” “. I was at Entebbe September 1 and spent

most of the three days there with Demos cleaning birds' nests off the airplane,"

Taylor said by way of a quick summary.

“The plane was a real mess; hadn’t been flown for a year and

a half. But we were lucky that the engines had been covered.” Then

he added with a characteristic expression, “ let’s back up

a while and get this lined up right.” Referring back to the phone

call, Taylor said Demos could not say much more than that the flying would

be in Africa and Europe, and he had to know at once if Taylor was available.

The response was affirmative. But almost as soon as he hung up the phone,

Taylor encountered a possible snag. Getting out his passport, he realized

it had run out, beyond the expiration date. So like other knowledgeable

Minnesotans who encounter such problems, Taylor contacted Senator Hubert

Humphrey’s local office in the Federal Courts building in Minneapolis;

and the renewal was arranged about as fast as Taylor could get downtown

to pick up a new passport. He then caught an airline flight, as instructed

by Demos, and reached Zurich on August 26.

The big rush turns into a long wait.

DESPITE the frantic effort up to that point, the situation reverted quickly

to a pattern that is all too familiar to corporate pilots. It might be

“fly on demand” sometimes; but it is just as likely to mean

"wait on demand” or “hurry up and wait" from the

military jargon. For the next four days, everything was at a standstill.

Demos and Taylor stood around waiting for instructions, and even sneaked

in a short sightseeing trip. Then they got word to proceed, again by telephone.

That call was from the international contact man whom Taylor refers to

as "the broker in Zurich." The two fliers were told where to

pick up necessary documents, maps, landing data, clearance papers, and

permits to get fuel at several points, specifically including Khartoum

in the Sudan and Luxor in Egypt. In addition, they were directed to what

seemed like a round-about itinerary. That’s nothing new for corporate

pilots, who often are ordered to go from A to B by way of C in the opposite

direction. It did, however serve to confirm that the forthcoming mission

was out of the ordinary. “That was August 31,” says Taylor,

referring to penciled notes in his black covered notebook. “The

word from the broker’s office was for us to go to London and then

get over to Sanstad, an airport used by the military and by some foreign

airlines that carry mostly cargo and do not operate through Heathrow.

We flew commercial to London and hired a taxi for the ride to Sanstad,

about 60 miles, I'd say." There the two Americans boarded a 707 of

Uganda Airlines for the long flight to Entebbe. At the central African

airport they saw first-hand some remaining evidence of what newspapers

all over the world had been reporting for several weeks. There was wreckage

and building damage from the July 4 commando action, and Russian planes

as well as Soviet personnel all over the airport. “Our contact was

with the Entebbe airport director, who told us he was a commander in the

Uganda air force and a special aide to Idi Amin, the country's strongman

president," Taylor told Pro Pilot. “And we were introduced

to a mechanic who also was there on instructions from Zurich to help us

get the Westwind ready to fly again.” Taylor thought the airport

commander 50 seemed well aware of the arrangements to “ repossess”

the airplane and get it out of the country. But most other airport personnel

in lower echelon jobs apparently didn't knowwhat was going on. They went

about their usual tasks without paying any particular attention to the

newly- arrived foreign "crew" working on Amin's jet. “We

did run into some people who said they had been around Entebbe about the

time of the July 4 raid that got out the hijack hostages, but most of

the Ugandans were edgy and we didn't press anyone for details. It didn’t

look like the smart thing to do, and we had plenty of a job ahead with

that airplane,” Taylor said. Aware or not of what was happening,

nobody interfered with the work and some were helpful when asked to assist

with errands or specific duties. Taylor thought the mechanic was competent,

but rather slow and not too familiar with the Westwind or 1121 Jet Commander.

"We were on Entebbe from September 1 through September 3," said

Taylor, referring again to his notes. "It took us all of three days

to get the plane ready to fly, including a short test hop. That plane

needs a lot of power for starting, and the batteries had been out of use

for so long that they weren't much good. We finally got it started with

a battery borrowed from one of the Russian aircraft.” The test was

hardly an ordinary flight, either, according to the pilots. One thing

that may explain it, Taylor thinks, was that on Friday, September 3, he

and Demos brought their suitcases from the hotel and stowed them in the

aircraft. They still didn’t have the go-ahead or specific orders,

but wanted to be ready, like good corporate pilots. The natural effect,

however, was that some airport workers got the idea they were about to

leave for good. “We had been cleared for the test by the airport

commander,” Taylor said, “but the operations people probably

didn’t know that and certainly didn’t act like anyone who

wanted to release the aircraft. If they really knew their stuff, they

would have realized there wasn’t enough fuel in the tanks to go

very far anyway.”\

It took a little discussion to convince them that the trial flight would

be OK, and Taylor began to move the plane. But before they got to a takeoff

position, a car pulled alongside and four huskies in Uganda army uniforms

got out and announced that they had been assigned as bodyguards for the

two fliers. "Looking at those four guys, with their guns at the ready,

what could we do but welcome them aboard?” Taylor asks philosophically.

“Of course, we did try to explain and warn them that there might

be some risk because the airplane hadn’t been flown for such a long

time, so we couldn’t be absolutely sure everything was in good working

order. They didn’t take our advice, and all four of them got into

the airplane anyway, with their guns in hand. “I checked with the

tower and was taxiing for take-off when all of a sudden a MiG-21 whipped

into position ahead of us. Then we spotted this other MiG waiting on our

tail, like ready to follow,” Taylor added.

Test flight proceeds with MiG escort

“THE CONTROLLER assigned us a quadrant out over the water, from

170 to 220 degrees. Those guys in the MiG’s were up there flying

around us all the time,” he said. According to Taylor’s notes,

the test hop lasted 45 minutes and they only went to about 14,000 feet

when they were satisfied with the aircraft’s performance. Returning

to Entebbe airport, the Westwind was escorted right down to the deck behind

one of the Russian MiG’s. “The other guy behind us didn’t

land right away, but he really buzzed us with a low pass over our runway,"

Taylor recalls. Summarizing the situation up to that point, Taylor said

he and Demos weren't getting much information about what to do or when,

but they were “traveling first class” all the time around

Entebbe. After the test, Taylor figured they might as well go back to

their hotel, the Lakeview, within three miles of the airport and overlooking

famous Lake Victoria. They described it as a beauty spot, and the attention

given to them personally was “Class A.” That was apparently

a result of the word going around that the two foreigners were guests

of Idi Amin himself. As the pilots were about to leave the airport, the

commander said a casual “goodnight” then added, “I’ll

see you at “0830 tomorrow.” Meager information though that

was, it had a kind of professional and official sound. Adding that later

to what they could surmise from newspaper and television reports, Demos

and Taylor figured there would be some activity around the airport the

following day, and they were not disappointed. Back at the terminal by

the suggested time Saturday morning, September 4, the pilots faced reporters,

TV cameramen, and “official” photographers for Uganda TV.

The airport commander managed to advise them against talking too much

to the media people, but they did get pretty thorough photographic coverage.

Finally the activity around them subsided, and they got into the aircraft

again, this time without any volunteer bodyguards. Taylor was in the left

seat, and they filed for Khartoum and Luxor as likely fueling stops and

Athens as their destination. They intended to top off the tanks frequently,

figuring that fuel cells had been dry so long, they couldn’t be

too sure about taking on the actual volume for which that plane is rated

with its extra tanks for long range. The morning was practically gone

when the tower assigned them a runway about 11 am. The Westwind made a

routine takeoff without being sandwiched between any other planes. Taylor’s

log shows that they covered the first leg, 980 nautical miles from Entebbe

to Khartoum, in two hours, twenty-six minutes. After a quick fueling,

they were soon airborne again on the way to Luxor, about 700 miles and

one and a half hours flying time. “We did negotiate an equatorial

front on that segment,” Taylor said, “but everything went

pretty good. Radars worked OK, and everything else. We used 41,000 a good

part of the time.

Another hijacking, and flight plan is changed IT WAS RON at Luxor, and

departure from Egypt the next day with the tanks again topped off by using

the credit arrangements and fuel permits that they had been carrying from

Zurich. Winging over the Mediterranean, everything had to be changed as

they encountered a situation that was making radios crackle in every country

of that area but had no direct relationship to the Demos-Taylor operation.

It was the kind of coincidence that could hardly be imagined and could

not have been controlled even if they had anticipated it. Taylor’s

recollections of Sunday, September 5, are much like the news reports for

that day. They were getting warnings of one airport after another being

closed throughout the region. The reason for the shutdowns, however, was

on the ground at Laranica airport on Cyprus; and that’s where Taylor

and Demos put the West- wind down. A KLM DC-9 was being held there after

considerable wandering under control of hijackers over Spain, France and

other countries. “We were waiting there when the DC-9 got cleared

to take off. It must have been 1100 hours, because that’s when anything

and everything seemed to happen to us. The DC-9 headed down the runway,

and from the chatter we could pick up nobody seemed to know where they

were going, but there were rumors about Tel Aviv,” Taylor said.

“We got cleared to go next and were rolling on a taxiway when operations

called us right back. They said Tel Aviv, which we had requested, was

shut down tight. (News reports for that day said Israel had denied landing

to the DC-9 because of a bombing threat and had blocked all airports with

trucks and tanks parked on the runways.) We just sat around at Laranica

a couple of hours, to around 1400 hours, when there comes the KLM DC-9

back. As soon as it landed, that airport was shut down tight, too.”

Newspaper reporters and TV crews crowded around as close as they could

get to the hijacked DC-9, and they were kept so busy that Idi Amin’s

personal jet and its American bizav pilots got rather slight attention.

Actually, the news media had gone to Cyprus to cover a hot political election,

and the hijacked KLM flight was just an extra bonus of news for them.

Before that day was done, release of the passengers was negotiated there.

Taylor still gets a chuckle from a sideline incident reported in a newspaper

he collected during the Mediterranean adventure. The report was that the

KLM captain recognized one of the hijackers and said to him, “I

think I’ve seen you before.” The hijacker was quoted as replying.

“you probably did. I hijacked you about four years ago on a flight

to Tel Aviv.” That story is perhaps typical of the kind of events

that kept newsmen busy at one spot and prevented most of them from thinking

of the Westwind as anything more than one more transient aircraft tied

up on Cyprus. By Monday, September 6, the hijack problem of that weekend

had been cleaned up, and planes were being allowed to leave when ready.

Again the action must have been around 11 am when the Westwind took off

for a short flight to Tel Aviv. Once under Israeli control, however, Taylor

and Demos were kept circling in a holding pattern for a good 35 minutes.

Lod tower was plainly upset and let them know it. They had not filed 24

hours ahead as required by Israeli security. “But the delay disappeared

as soon as we were on the ground,” Taylor said. “Two guys

greeted us and they had already taken care of the details in customs.

They steered us around the news media people, sort of through the back

door at immigration, and we got through in no more than 10 minutes. In

plenty of time for lunch in Tel Aviv,” said Taylor as a windup of

his Uganda-lsrael mission. With the Westwind “repossessed”

by the Israelis, the job of the "corporate” pilots from MSP

was terminated. They took airline flights again, Demos to Zurich and Taylor

to Frankfurt. From there he continued on schedules, flying Lufthansa to

Chicago and making a connection for home in Minneapolis.

Taylor had nothing but good words for the Westwind, saying it functioned

almost perfectly for a plane that had been sitting idle for so long that

the dirt looked like birds' nests on it. As to political background of

the mission, he preferred to keep low but did deny newspaper reports about

big payments to him and Demos through mysterious Swiss bank accounts.

On Friday, September 10, Taylor was having lunch with pals in the Minnesota

Business Aircraft Association who were at their regular monthly meeting

that day. He was wearing a dark blue blazer and gray slacks, the kind

of outfit that has given Carl Taylor a reputation as a natty but modest

dresser. The joking that went on about hurried international phone calls,

skimpy orders and flight plan changes sounded typical of the “fly

on demand" nature of corporate aviation. Only the international implications

made it different from “your everyday corporate job,” to repeat

Taylor’s description. One pilot quipped that Taylor hadn’t

even been gone long enough to quality for the 14-day excursion fare. Taylor

did bring back one souvenir, a picture of Idi Amin that he took off the

wall panel of the Westwind. He was pretty sure the Israelis wouldn’t

care, as long as they had their jet back.

PROFESSIONAL PILOT / December 1976.